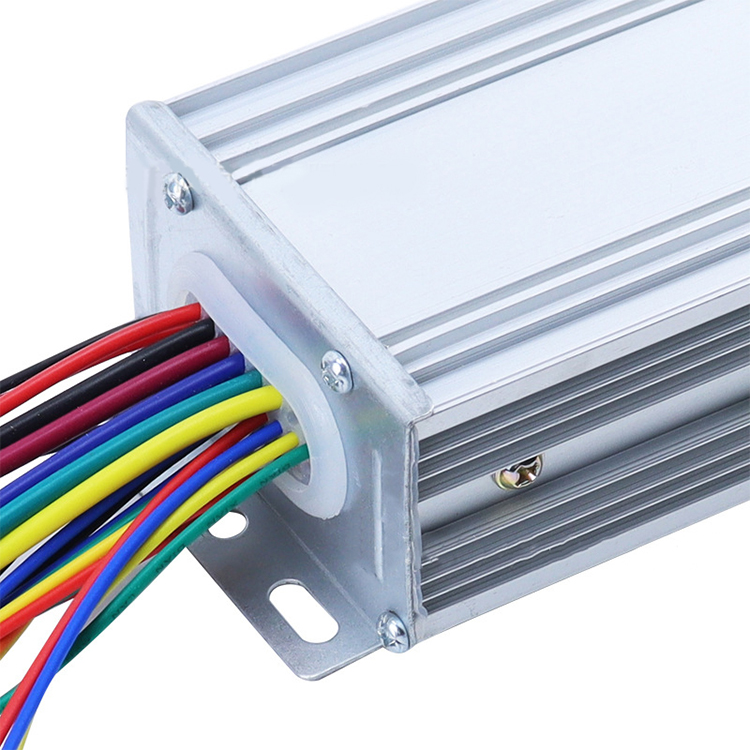

The Electric Vehicle Controller is a complex assembly of electronic and cooling components housed in a protective enclosure. Its main subsystems include:

Power Stage (Inverter Module): This contains Insulated-Gate Bipolar Transistors (IGBTs) or Silicon Carbide (SiC) Mosfets. These high-power semiconductor switches rapidly turn on and off to convert DC to AC (pulse-width modulation).

Gate Driver Circuitry: This component translates low-voltage control signals from the microprocessor into the high-current signals needed to reliably switch the IGBTs/Mosfets on and off.

Microcontroller Unit (MCU): This is the central processor that executes the control algorithms. It receives inputs from sensors (throttle position, motor speed) and calculates the precise timing and magnitude of the switching signals to deliver the requested torque and speed.

DC-Link Capacitor Bank: Large capacitors that smooth the high-voltage DC from the battery, filtering ripple and providing a stable local energy reservoir for the rapid switching of the power stage.

Cooling System: A liquid-cooled cold plate or an integrated heat sink is essential to dissipate the significant heat generated by the power semiconductors during operation.

Sensors and Communication Interfaces: Components for monitoring current, voltage, and temperature, along with communication buses (like CAN) to exchange data with the vehicle's main computer and battery management system.

The controller is a necessary enabler of the electric drivetrain, fulfilling several core functional requirements that batteries and motors alone cannot.

Precise Motor Control and Torque Regulation

The primary reason for its existence is to provide accurate control of the electric motor. The controller interprets the driver's accelerator input as a torque demand. It then calculates and generates the specific three-phase AC waveform (frequency, voltage, and current) required to make the motor produce that exact torque and rotational speed, enabling smooth acceleration, cruising, and deceleration.

Enabling Bidirectional Energy Flow and Regenerative Braking

The controller is designed to operate in two directions. During acceleration, it draws power from the battery to drive the motor. During deceleration or braking, it can reverse its function, acting as a rectifier to convert the AC generated by the motor (now acting as a generator) back into DC to recharge the battery. This regenerative braking function improves energy efficiency.

Protecting Components and Ensuring System Safety

The controller continuously monitors system parameters like current, voltage, and temperature. If it detects an unsafe condition—such as an overload, short circuit, or overheating—it can instantly limit power or shut down to protect the battery, motor, and itself from damage. It also provides critical isolation between the high-voltage traction system and the low-voltage vehicle network.

Producing reliable, high-performance controllers at scale presents significant engineering and operational challenges.

Thermal Management and Reliability: Managing the substantial heat generated by power semiconductors (IGBTs/SiC) is a persistent issue. Inconsistent thermal interface materials, poor solder joints under the modules, or imperfections in the cooling plate can create localized hot spots. These hotspots accelerate component aging, reduce efficiency, and are a leading cause of field failure. Achieving uniform heat dissipation across all power switches requires precise manufacturing and assembly processes.

Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) Control: The controller's high-frequency switching creates significant electromagnetic noise. Containing this EMI within strict regulatory limits to prevent interference with other vehicle electronics (like radios or safety systems) is a major design and manufacturing challenge. It requires careful board layout, the use of shielding cans, and consistent assembly of filters and ferrite cores. Variations in component placement or shielding can bring about EMI compliance failures.

High-Voltage Isolation and Safety: The controller must maintain robust electrical isolation between its high-voltage sections (hundreds of volts) and the low-voltage control circuits and metal chassis. This involves using specially designed isolation components, conformal coatings on circuit boards, and air/creepage gaps that meet stringent safety standards (e.g., ISO 26262). Any contamination (dust, moisture) or defect in these insulating materials introduced during manufacturing can compromise safety and bring about catastrophic failure.